The Perfect Game

Kyle Keiderling

In college basketball lore, it’s been called “The Game of the Ages,” “The Greatest Upset in the History of the NCAA Tournament,” and “The Perfect Game.” Award-winning author Kyle Keiderling opted for the latter in his fantastic new book The Perfect Game. It chronicles in a definitive voice Villanova’s improbable two-point upset of the Georgetown Hoyas in the 1985 NCAA men’s basketball championship finale. Keiderling skillfully hits the rewind button and delivers many an unknown tale. Among the best is his story of visiting a few years ago former Villanova coach Rollie Massamino at his Florida home to interview him about his team’s championship run. Tucked under Keiderling’s arm was a videotape of the crowning moment of Massamino’s coaching career. “I wanted Rollie to walk me through the chess match,” Keiderling recalled. “When I suggested that we pop the tape into the VCR, Rollie looked at me blankly.

“I’ve never seen the game,” Rollie said.

“What?” I answered. “You won the national championship.”

“No, I’ve never seen the game.”

“Why not?”

Rollie looked at me and said, “I was afraid we might lose.”

Keiderling recently spoke with D.C. Basketball about his book, the game, and the memorable cast of characters. So pull up a chair. Let’s travel back in time to 1985. Ronald Reagan sits in The White House, John Thompson still rules the Hilltop, and America is about to be treated to The Perfect Game.

The Coaches

--Where did you get the idea to write The Perfect Game?

On a golf course in New Jersey. I had just finished my book on Hank Geathers [the late Loyola Marymount star], and I was out playing golf with some buddies. In the foursome was a graduate of Georgetown and one from Villanova. Both said, “Kyle, why don’t you do a book on the Georgetown-Villanova game?” I remember thinking, “Not a bad idea.” The game remains the greatest upset in the history of NCAA tournament. The protagonists include Rollie Massamino, John Thompson, Patrick Ewing. Great story, great cast of characters. So, I said, “All right.”

--Did you interview John Thompson?

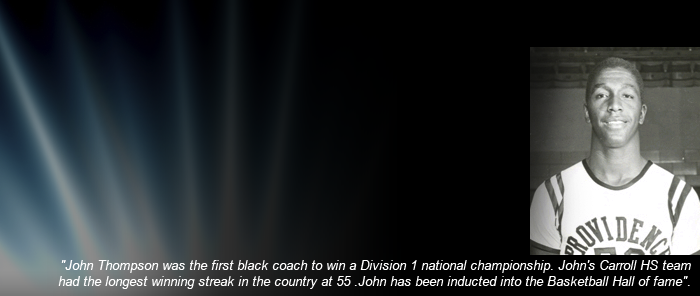

No, Thompson refused to talk to me. Actually, I shouldn’t say he refused. Thompson never responded to my repeated requests for an interview [laughing]. So I had to do a lot of research on Thompson myself via the ProQuest news library. I also read the book Big Man on Campus, talked to reporters, and did all of the usual digging that writers do. My research forced me to confront a lot of my preconceived notions about John Thompson.

--Such as?

Well, I came to the table with the typical Caucasian view from that era. I thought Thompson was a six-foot-ten, brawling, snarling, angry black man who hates the press and everything else in his path. His was a circle-the-wagons mentality. Us against the world. That’s the cultural baggage that I brought to the project, for better or worse.

--And what did you discover?

The baggage and its contents were simplistic, to say the least. To begin to understand John Thompson, you must start by wrapping your brain around the segregated Washington in which he was raised. This separate-and-unequal environment formed him in much the same way as Rollie Massimino’s warm, fuzzy, open-armed, manja-manja Italian family formed him. But I kept digging deeper to “get” Thompson. I finally had my epiphany. It came in an interview when I asked a source what he thought of John Thompson. His answer sums up the man perfectly. He said, “John is easy to hate, but he’s hard to know.”

--For outsiders, so were his Georgetown teams.

Exactly. Thompson built his team in his own “easy to hate but hard to know” image. There’s NO question about it. George Leftwich, who played in high school with Thompson and later coached against him in the Catholic School League, said the same thing. George told me that every team that John Thompson has ever coached, from high school through Georgetown, has carried his edge.

--What are the elements of that edge?

Well, it starts with power and intimidation. Thompson usually had a dominant post player whose mere presence in the lineup forced the opposition away from the basket on offense to attempt longer, lower-percentage shots. Advantage Thompson. Another element was extreme defensive pressure. Thompson always unleashed the hounds. He put opponents on their heals from the opening whistle to break them with his superior team speed, quickness, and tenacity.

--He took no prisoners?

Right. While on the hunt, Thompson had his players primed to bump, shove, elbow, and maybe break a few kneecaps. Whatever it took to win. If opponents didn’t like it, well, tough. If they were intimidated, that’s even better. In fact, Georgetown had most of its games won before the opening tap. That’s how intimidating they were.

--The irony is Thompson was no fly swatter or speed merchant when he played in the 1960s.

True. Thompson was not a particularly gifted athlete. It took a lot of hard work for him to become a basketball player and earn high school All-American honors in his senior year.

--And Thompson was surrounded by truly outstanding talent at Bishop Carroll High School, such as George Leftwich, who demanded the ball, too.

Absolutely correct. But Thompson haunted the playgrounds of Washington, D.C. on his own as a teenager. After Carroll lost in the City Championship game, I believe it was during his sophomore season, Thompson carried a newspaper clipping of the defeat in his wallet as motivation. He would go to the playgrounds and shoot . . . and shoot . . . and shoot. Thompson became such a playground gunner that nobody wanted to play with him anymore. But Thompson seemed to know that he had to develop his hook shot and inside game to ensure that Bishop Carroll got better and didn’t lose another championship game. And Carroll didn’t. But that’s an example of Thompson’s will power and unrepentant, try-and-stop-me edge.

Not to make this interview all about John Thompson, but let me go back to a point that I started to make a moment ago before we move onto the Xs and Os of the championship game. That is, I entered this project viewing both coaches in the same overly simplistic way that I think most whites did back on that fateful night in 1985. According to that dusty worldview, Rollie Massimino wore the white hat, and John Thompson rode into town under the black hat. I mean that in the Wild West sense, not racially. What I found is that between these black-and-white generalizations lies a whole lot of gray.

--How so?

Take Rollie. He used the Italian family touchstone, which was a major formative element in his life, to mold a very talented team into a cohesive unit. He referred to this Villanova team – and they do so to this day – as a family. Now take Thompson. He took his aforementioned edge and rallied his group of extremely talented players (and there were five future pros on the roster) in this way. Nobody likes us. Everybody hates us. We’re going to circle the wagons. It’s us against the world. In other words, these were the formative touchstones of growing up black in segregated Washington, D. C. These touchstones, too, were applied to build a cohesive family environment. So, if you think about it from a psychological standout, both coaches were doing very similar things.

--It was unity by different means.

And that sums up part of the gray that I mentioned. Thompson’s kids never called him Coach. It was always Mr. Thompson. Do you know what Rollie’s kids called him? Daddy Mass. Both coaches projected larger-than-life personas and then used the elements that buttressed these projections to create identity and cohesion among talented, but egotistically diverse, players. And the proof is in the pudding. In three of the four seasons leading up to this 1985 championship game, Georgetown advanced to the Final Four. At Villanova, although Rollie didn’t reach the Final Four until 1985, he always managed to get a couple of rounds of the NCAA Tournament under his belt.

Here’s another gray area. John Thompson was loud. He was profane. He was a bully. He was belligerent. He was all of the above - and then some. But Thompson kept a deflated basketball on his office desk. The thing was as flat as a pancake. People would walk into his office and ask him, “What’s up with that?” His standard answer: There’s more to life than basketball. Thompson and Massimino made sure their players got their degrees and were on track to succeed in life. I asked some of their former players about it. They told me that they owe everything to Mr. Thompson and Daddy Mass.

--So both coaches walked the walk?

Definitely. The thing is outsiders didn’t see this very real side of John Thompson. They saw what I saw for all of those years while he angrily roamed the sidelines with the white towel slung over his shoulder. But when Thompson arrived at Georgetown, he wrote handwritten letters to the parents of his players at the end of each semester to keep them apprised of their progress. The letters never mentioned basketball. The topic always was education.

The Matchup

--Let’s jump to the 1985 NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament. Georgetown is the defending NCAA champion, and senior center Patrick Ewing will soon be named the

Naismith College Player of the Year. The Hoyas enter the tournament with 30-2 regular-season record and are the first seed in the East Region.

All correct, and Georgetown was such a prohibitive favorite entering the 1985 NCAA Tournament that the event was largely considered a coronation. Nobody – and I mean nobody – in the media gave anybody a chance against Georgetown. What’s more, nobody wanted to play Georgetown. Lou Carnesecca, the coach of St. John’s, said after getting blown out by Georgetown in the semifinals, “It was like facing the Panzer division and Luftwaffe all at once.” Keep in mind, this was a great St. John’s team, featuring Chris Mullin and Walter Berry. But here’s the kicker. After Villanova’s 52-45 semifinal upset of Memphis State, Rollie told me he preferred to play Georgetown, not St. John’s, in the championship game.

--You’re kidding?

No, I’m not. Rollie felt Villanova matched up better with Georgetown.

--But the Villanova scouting report before the championship game wasn’t too terribly optimistic.

That’s right. Mitch Buonaguro, then the Villanova assistant coach and now the head man at Sienna, prepared a scouting report for the game. Now, when you read the scouting report, which is printed in full in my book, you wonder how in the hell the Villanova players could have ever believed they belonged on the same court as Georgetown. I mean, their own scouting report makes Georgetown sound like The Second Coming.

--Villanova and Georgetown, though, had faced off twice during the Big East regular season. My recollection is Villanova held its own.

You’re right. Although Georgetown won both games, they were fairly close contests. But there is a major asterisk here. You may recall that the NCAA decided that season to experiment with the then wild-eyed idea of a shot clock. They chose the Big East Conference to conduct the experiment, and Villanova lost twice with the shot clock ticking in the background. The shot clock would be turned off for the championship game. If you recall, the Villanova-Georgetown final marked the last college game to be played without the shot clock.

--And, with the clock off, Daddy Mass believed Villanova could win?

Exactly. Rollie was a defensive-minded coach. He employed multiple defenses and could disguise them well. So Rollie was confident that he could keep Georgetown guessing. On the other end of the floor, minus the shot clock, Rollie could milk each offensive possession, slow down the game, and take Georgetown out of its rhythm. But there was another key factor in play?

--What was that?

Three of Villanova’s stars had played against Patrick Ewing and the other Georgetown guys for years at Howard Garfinkel’s Five Star basketball camp in the Poconos. So, the intimidation factor wasn’t there for Villanova. There’s also an interesting side story here. At the Five Star camp, then high school guard Gary McLain convinced forwards Dwayne McClain and Eddie Pinkney to attend Villanova with him. The trio formed what they called “The Expansion Crew.” The idea being, they would expand Villanova’s basketball horizons. Four years later, the Expansion Crew had expanded their way to the 23,500-seat Rupp Arena in Lexington, Kentucky to compete for the NCAA championship, college basketball’s greatest stage and ultimate prize. And on that Monday night, the second-largest television audience ever to view an NCAA championship game tuned in for what was supposed to be Villanova’s funeral.

One final point. Villanova entered the tournament as the eighth seed in the Southeast Region. Had the NCAA not expanded the tournament to 64 teams in 1985, Villanova would have never gotten an invite to the Big Show. Villanova had 10 regular-season losses. In 1984, that would have bought them a ticket to the NIT.

--Just out of curiosity, what was Georgetown’s scouting report?

I doubt Georgetown’s scouting report was anything too awe inspiring. As mentioned, Georgetown had played Villanova twice, beaten them twice, and were pretty confident about their ability to repeat as national champions. In fact, Craig Esherick, then Thompson’s assistant, told me Georgetown really didn’t do anything differently in preparation for Villanova. The game plan was full steam ahead.

The Perfect Game

--Let’s go to the championship game. Why don’t we start the ball rolling with an excerpt from The Perfect Game:

After Patrick Ewing knocked the opening tip-off out of bounds, Villanova got the ball. Gary McLain took over, and the start was not what the ‘Cats had hoped for. Villanova turned the ball over on an errant pass against the 1-3-1 zone of Georgetown . . .

Georgetown pressured McLain, but he managed to bring the ball up court, and Georgetown was in a man-to-man defense this time as Villanova worked the ball around the top of the key. Then Dwayne McClain shook loose and launched an awkward, off-balance jumper. It was a low liner that somehow went in. Wildcats by 2.

Georgetown came right back and after two or three passes found Reggie Williams open on the left side in the corner. He drained a jumper to tie it again at 6. Once again, the scouting report was right: Williams “shoots the ball extremely well from the corner.”

After Baby-Face McLain beat the full-court press up court, he got the ball to Pinkney, who travelled while trying to go around Ewing. Another turnover by Villanova. Georgetown inbounded the ball and found Ewing at the top of the key, where he put up a jumper and missed. Billy Martin grabbed the rebound and converted. Hoyas by 2.

--A minute later, Rollie Massimino does the unexpected.

Right, Rollie subs in sophomore Harold Jensen. There’s an interesting backstory here. Jensen was a high school All American out of Trumbull, Connecticut. But Jensen’s confidence and jump shot had escaped him since he arrived at Villanova. Jensen was down deep in the dumps. Daddy Mass had spent untold hours counseling, encouraging, and crying with him. But Rollie hardly ever played him. That is, until the tournament. Jensen got his chance to play a few meaningful minutes in the early rounds of the tournament. Against Georgetown, four minutes gone in the first half, Rollie walks down the bench, puts his hand on Jensen’s shoulder, and says, “Harold, you’re in.”

Craig Esherick remembers thinking, “This is great.” He thought the untested Jensen would be easy to spook, and he would start throwing the ball into the third row. Well, little does Esherick know, Massamino had told his players after the team dinner the night before to go up to their rooms, switch off the lights, and imagine everyone of their shots swishing through the net. Jensen had followed Daddy Mass’ advice. When Rollie tapped him on the shoulder early in the biggest game of his career, Jensen told me his old confidence from high school magically reappeared.

--Let’s put Harold Jensen on hold for a minute and move to Baby-Face McLain. If you pay close attention as the first half unfolds, something strange was happening. Georgetown had turned up its usual take-no-prisoners defensive pressure, but McLain had for the most part withstood the heat.

Gary McLain had a baby face, but he possessed the heart of an assassin. Gary McLain was NOT going to get rolled by Reggie Williams, David Wingate, and rest of the Georgetown defense. McLain orchestrated the twelve or fourteen passes that Villanova made on every single offensive possession before attempting a shot. What’s more, he did so flawlessly.

--Without McLain, Villanova crumbles in the first half?

Right, Gary was the principle reason that Villanova won the game. Georgetown couldn’t rattle him.

--What about McLain’s subsequent admission that he played the game high?

That’s a little tricky to answer, but I’ll try. As I said, Villanova was a family, and every family has a wayward child. Villanova’s wayward child was Gary McLain. Gary grew up in the projects in The Bronx and had seen it all. He was a tough, tough kid. The irony is, here is this tough-as-nails kid, and he’s the one on the team to succumb to drugs. Gary later wrote a lengthy expose about it in Sports Illustrated that indicated he was high for the Georgetown game and which also claimed he was under the influence at The White House when the team met President Reagan. The rest of the team, by the way, doesn’t buy it. They don’t believe he was as drug addicted as he claimed. They also are very hurt by his actions. Gary allegedly got $35,000 from Sports Illustrated for that article. Now, I talked to Gary McLain three or four times for The Perfect Game but never interviewed him. He supposedly didn’t have time. But Gary is now a drug and alcohol-abuse counselor in Florida, about fifteen minutes away from Rollie Massimino. So, Gary is cleaned up and sober.

--At halftime, Villanova holds a hard-fought 29-28 lead. You write in the book, “Brent Musburger told the vast television audience, “The first half was as good a half of college basketball as I’ve ever seen.” The second half would be even better. Let’s flip to midway through the second half and another excerpt from The Perfect Game:

After two passes Gary McLain was in the clear and lofted a jumper from outside. Good! That put Villanova up by 1. Gary pounded his fist as he passed the Villanova bench and flashed a smile at his coach.

Georgetown worked the ball until Patrick Ewing took a short shot and missed. Billy Martin got the rebound, took it up in traffic, and was fouled. Ed Pinckney picked up his third foul.

On his bench John Thompson anxiously wiped his brow. Martin made the first free throw, tying the game. The second shot also was good, which put Georgetown back in front. The relentless Hoyas again put on full-court pressure as Jensen got the inbound ball to Gary, who brought it up court, waving Jensen out of the way.

Villanova made three passes on the perimeter until Gary found Jensen on the left wing with some space. McLain fired to Harold, who put up an eighteen-footer. Good!

--McLain and Jensen were the story of the second half for Villanova.

Yeah, I think Gary had two turnovers in the second half. Villanova took eleven shots from the field. They made ten. Jensen took five of those shots. He made them all. Esherick told me, “Everyone of Jensen’s shots felt like a dagger to our heart.”

--Could you imagine eleven shot attempts in a half today?

Hell, today Villanova might jack up eleven shots in the first two minutes. The fact is: Rollie knew what he had to do. If you watch the film of that game, there’s the seven-foot Patrick Ewing, arm held high on the block, and the Georgetown guards are trying mostly unsuccessfully to dump the ball inside to him. Over and over again. Rollie had six-foot-nine Eddie Pinkney and six-foot-seven Harold Pressley clamped around him. Both went on to play in the NBA. Pinkney told me that he LOVED to play against Ewing.

--Why?

I said to Eddie, “Why Ewing? He has the wing span of a B-52.” He answered, “I always wanted to test myself against the best. And Patrick was the best.” That was the determined mindset clamped onto Ewing’s strong side, while Pressley dropped down from the weak side to squeeze Ewing into an uncomfortable two-man vice. Ewing wasn’t used to being squeezed like this. So, as the minutes tick down in the second half, you can see Ewing creep further and further away from the basket on offense to get the ball. Patrick Ewing under the basket was a force that no one in the college game could stop. But out by the foul line and beyond, which is where Villanova rode him, he was an average player. Watching the film, you can see him grow frustrated. And more frustrated. Rollie, as planned, took Georgetown out of its comfort zone.

When the game ticks down to about three minutes left, run-and-gun, in-your-face Georgetown suddenly spreads the floor and goes into a slowdown, four-corners offense nursing a two-point lead. I asked Craig Esherick, “What was this all about?” He told me Thompson had been an assistant coach under former North Carolina legend Dean Smith on the 1976 United States Olympic team. Smith taught Thompson his four-corners offense. Esherick said Georgetown had used it in the past and felt comfortable doing so. Well, the four-corners offense lasted about twenty seconds. Georgetown threw the basketball away – and that spelled their doom.

--What did the Villanova players think when they saw the four corners?

One of the players told me, “We were happier than hell to see them do it. It gave us a chance to rest.” He also said, “We knew then that we had Georgetown right where wanted them.” The idea being, Georgetown had no more fight left in them. They were waiting for the clock to expire.

--But, going back a few frames, Thompson saw Ewing getting pushed further from the basket in the second half. He apparently made no countermove to rotate Ewing back

into the block. Why?

I don’t know. But I can tell you, Thompson pulled Ewing from the game and lectured him. He presumably told Ewing to stand his ground. I mean, Pinkney and Pressley kept pushing and pushing and riding the B-52 right off the block. As I said, Ewing finally retreated to the foul line to free himself from the pressure. If you watch the tape, there are a couple of four or five-minute stretches, especially in the second half, when Ewing doesn’t touch the ball. He’s either blanketed inside or out of position. Villanova’s defense literally took him out of the game in the second half.

--Let’s go the final seconds, and another excerpt from The Perfect Game:

As play resumed, Jensen accepted the ball from the referee and the responsibility that went with it. All he had to do was get the ball to a Villanova player and let the two seconds tick away. But if he failed to make the pass or the Hoyas managed to intercept it under their basket, they might be able to convert and tie the game.

During the time-out Rollie had stressed the danger of the situation. “It’s a different story now. They can tie. We need to get the ball in,” he told his players.

He told the ‘Cats that Harold should get the ball to Dwayen or Gary. If that proved impossible, Harold was to get it to Ed, who would be waiting at half court.

As Harold took the ball from the official, Dwayne was standing just to his right, about ten feet away. “During the time-out, I told Harold, ‘No matter what, get me the ball,’” Dwayne said.

Jensen made the inbounds pass. As Harold did so, Dwayne was bumped from the side, tripped, and fell to the court just as Harold’s pass got to him. “As he threw it in, I tripped and went down. I’m thinking, ‘Just stay down. Don’t move or they will call a travel, and Georgetown will have the ball.’ I stayed down and hugged that ball,” Dwayne said.

The last two seconds of the Hoyas’ reign quickly evaporated. The buzzer sounded. There was no repeat.

--And across America, folks walked away from their television sets, to borrow Jack Buck’s famous line three years later, in various states of “I don’t believe what I just saw.”

Villanova 66, Georgetown 64.

Epilogue

--You titled the book The Perfect Game. Having dug deeper into the story, do you still consider it the perfect game?

Well, let me tell you about a conversation that I had with Dwayne McClain. I told him that the title of the book would be The Perfect Game. He said, “We had seventeen turnovers. How can you call that the perfect game?” [Laughing] But you know what? I lifted the title from P.J. Carlisimo, then the coach at Seton Hall. He said afterwards, “This is the closest thing that I’ve seen to a perfect game.” P. J. has watched a lot of basketball games in his time. Maybe he’s right.

--And is it the perfect underdog story, too?

Yeah, I like this story. I like it because I discovered things that I didn’t know about both teams. It’s always great when those long hours spent reporting and writing the book pay off. I want to encourage everyone to get their hands on the book and relive a true NCAA classic. Yes, Georgetown lost. But remember that deflated ball on John Thompson’s desk? Everybody is a winner here, and it’s worth remembering one of Georgetown’s greatest teams ever.

--Thanks for telling us about the book.

|

|

|

|